„Wenn Sie sich fragen müssen, was Jazz ist, werden Sie es nie erfahren.“

Louis Armstrong

Astral Project

Hi, folks,

Hi, folks,If you ever hear the expression "Jazz is dead," buy a ticket for an Astral Project concert and give it to the guy who is responsible for this statement (don't forget to buy one for yourself). If the person doesn't change his attitude after the concert, there is no way to bring this guy near to jazz

Unfortunately, the group is barely known in Europe, perhaps because the only way to buy their CDs is on the Web. Of course, the group has its own homepage (www.astralproject.com), through which you can buy their recordings.

Down Beat called Astral Project "one of the most distinctive and cohesive quintets in jazz of the '90s." Formed in 1978 from the cream of the New Orleans modern jazz scene, Astral Project has remained a unit even while its members have explored innumerable other endeavors, including recordings as leaders and sidemen for a wide array of major and independent labels. Through it all, the band known as New Orleans' Premier Jazz Ensemble has always regrouped to reach for the stars. Jazz Times has proclaimed Astral Project "one of the more adventurous working units in modern jazz today." It's all true, folks.

| Astral Project by Jonathan Tabak | TOP |

By Jonathan Tabak

What's behind Astral Project? What's behind the longest standing, most consistently innovative and compelling modern jazz band in New Orleans?

Over twenty years playing together for one thing. That in itself makes the band unique in a jazz world traditionally dominated by star-leaders, with various, interchangeable sidemen in supporting roles. But the leader-sidemen formula has always seemed at odds with one of the most exciting, essential objectives of jazz, and especially New Orleans Jazz: group improvisation.

Yes, of course, it's possible for a group of skilled jazz musicians who've never played together, or who have only played together a short while, to get up on the bandstand, dive into some familiar material, and suddenly find that magical, instantaneous communication, where, even as one player goes out front to solo, they all feel like they are hurtling through uncharted space as one entity. But that's rare and fleeting, isn't it?

If we could assemble the ultimate dream gig, with, say, Max Roach on drums, Charles Mingus on bass, Thelonious Monk on piano, John Coltrane on sax, and Miles Davis on trumpet, it would look fantastic on paper (and to a promoter). It would sell, but would it really jell?

In reality, how much more satisfying to listen to a group of seasoned pros who have spent, literally, half their lives developing the deepest,

most intimate musical relationship with each other, who have composed a truckload of original songs that are uniquely responsive to their

collective style and personality---songs which, like perpetually warm, soft clay, can be shaped and re-shaped according to the spirit of the

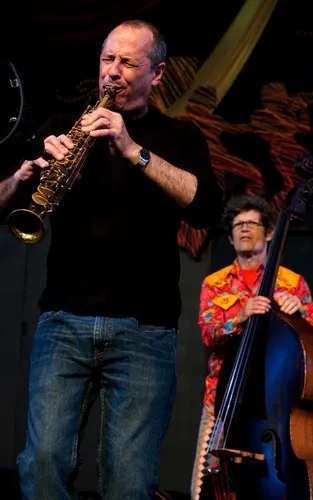

moment. How exciting to watch pianist David Torkanowsky suddenly lock eyes with drummer Johnny Vidacovich, and, in a fluid instant, they

react, and the song goes in a totally new direction, a direction which saxophonist Tony Dagradi had (consciously or unconsciously?) hinted at

in his solo, but it's a whole new ball game now, and Tony's free to enlarge his idea while bassist James Singleton subtly adapts the groove,

and guitarist Steve Masakowski realizes that a drone effect will create the perfect crescendo...

In reality, how much more satisfying to listen to a group of seasoned pros who have spent, literally, half their lives developing the deepest,

most intimate musical relationship with each other, who have composed a truckload of original songs that are uniquely responsive to their

collective style and personality---songs which, like perpetually warm, soft clay, can be shaped and re-shaped according to the spirit of the

moment. How exciting to watch pianist David Torkanowsky suddenly lock eyes with drummer Johnny Vidacovich, and, in a fluid instant, they

react, and the song goes in a totally new direction, a direction which saxophonist Tony Dagradi had (consciously or unconsciously?) hinted at

in his solo, but it's a whole new ball game now, and Tony's free to enlarge his idea while bassist James Singleton subtly adapts the groove,

and guitarist Steve Masakowski realizes that a drone effect will create the perfect crescendo...

With Astral Project, expect the unexpected; it's an ongoing process of discovery for both band and audience. "That's what makes it

interesting, the unpredictable nature," says Masakowski. "We really don't know what's going to happen."

Masakowski, who has put out several of his own records for Blue Note (What It Was, Direct AXEcess), is actually the junior member

of the band, having not joined permanently until the mid-eighties, but you would never guess from the seamless way he supports and

accents the music, and from the many stellar compositions he contributes to the band's repertoire. (He wrote the title cut

on their new album, VoodooBop, for example.) With his solos, he tastefully explores the extra range offered by his custom-built

seven string guitar. His fast, precise lines weave Greenwich Village sophistication, Latin swing and the tangy Southern blues

of his native New Orleans into a mellifluous whole. Like all five Astral Project members, he is a world-class musician, a

distinguished sideman, composer and leader who can work practically anywhere, but who always returns to Astral Project seeking a

new level of transcendence.

"You go on certain gigs or certain recordings and people want you to play well, they want you to support them, but they don't want every

bit of light that you have," says saxophonist Dagradi. "When you come on the bandstand with Astral Project, I want everybody to give

me everything. Give me everything you got. No limitations at all. And that's completely rare in this day and age, because if you go on most

any gig, everybody's got an agenda, parameters that they work in. We don't. Our parameters are that we can go anywhere and whatever you do,

you expect the band to support you. And they do. If, by just a couple notes sometimes, I indicate I want to go somewhere harmonically or

rhythmically or melodically, there will be somebody there in a nanosecond, going, 'Yeah, I'm there, too,' and you know that there's no

problem with it."

"You go on certain gigs or certain recordings and people want you to play well, they want you to support them, but they don't want every

bit of light that you have," says saxophonist Dagradi. "When you come on the bandstand with Astral Project, I want everybody to give

me everything. Give me everything you got. No limitations at all. And that's completely rare in this day and age, because if you go on most

any gig, everybody's got an agenda, parameters that they work in. We don't. Our parameters are that we can go anywhere and whatever you do,

you expect the band to support you. And they do. If, by just a couple notes sometimes, I indicate I want to go somewhere harmonically or

rhythmically or melodically, there will be somebody there in a nanosecond, going, 'Yeah, I'm there, too,' and you know that there's no

problem with it."

It was Dagradi who originally formed Astral Project back in 1978, not long after the twenty-four year old, Summit, New Jersey native first arrived in New Orleans following a touring stint with funk band Archie Bell & The Drells (famous for the hit "Tighten Up"). "I just thought I'd check out New Orleans for like a minute," Dagradi says. "I didn't think I'd like it here. The only thing I knew about it was Dixieland, and I didn't want to do that, but then I started working right away."

Dagradi quickly realized there was more to the New Orleans scene, and began actively seeking out the right players to form a band. "I needed a vehicle for me to present some of my own music, so I sat in with everybody that I could. I went to Lu and Charlie's, which, at that time, was the main jazz club. I sat in there almost every night. I also sat in at Tipitina's and clubs on Bourbon Street, until finally I met just about everybody that I know today. In a couple of months I really found a lot of people. I was trying to find a good combination to play with, and I picked Johnny [Vidacovich], James [Singleton] and David [Torkanowsky], and, at least at that initial stage, I wanted a percussionist, so I think it was James who suggested Mark Sanders (who left the band for New York in the eighties). I hadn't met Steve [Masakowski] yet, he was one of the few I didn't meet right away."

No stranger to Eastern philosophy, Dagradi named the band after his objective: to elevate participants from the "physical plane" to the more spiritually refined "astral plane," hence, Astral Project.

It's a mission which remained constant and intensified over the years, even as the band left behind its original sound. "My original direction for the band was more electric and fusion," Dagradi says. "I had James playing electric bass, and we did some covers of funk bands. I had some tunes then that were more pop-fusion, but it soon became evident that we were all of like mind and could go in another direction. Our hearts were really more into improvisational music."

At first, Dagradi was the only one composing new music and arranging gigs, but, after a few years, the others started contributing equally,

and the band's collective identity was forged. From that point forward, Dagradi says, Astral Project "seemed to have a life of its

own."

At first, Dagradi was the only one composing new music and arranging gigs, but, after a few years, the others started contributing equally,

and the band's collective identity was forged. From that point forward, Dagradi says, Astral Project "seemed to have a life of its

own."

Meanwhile, that time in the early eighties was also an essential growth period for the Astral Project musicians individually, as this is when they began separately gigging and recording with a wide variety of musicians. When Dagradi, for example, wasn't out touring with Carla Bley's band at that time, he was, like the others, playing all over town with James Booker, Professor Longhair, James Black, Alvin "Red" Tyler, Ellis Marsalis, Earl Turbinton... soaking up gallons of New Orleans' soulful influences (R&B, funk, soul, second-line, etc.), while also learning how to adapt to almost any musical situation.

As the young men branched out and developed into "first call" sidemen and leaders themselves, Astral Project became an artistic haven, where, free from the restrictions of specific genres or a leader's requirements, they could experiment with new ideas and influences in a totally supportive, comfortable environment.

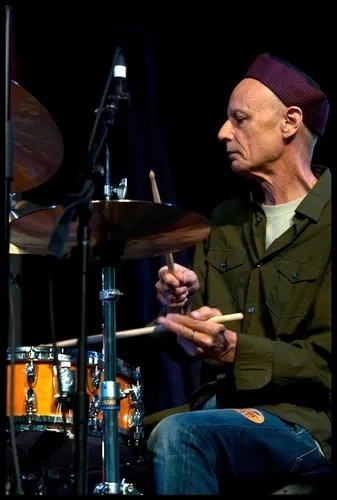

"It's like going to a family dinner, as opposed to going to a formal dinner, you know?" says Johnny Vidacovich in his infectious New Orleans drawl. "I mean, you go to a formal dinner, you're thinking, I got to sit straight and watch my manners. You go to a family dinner, man, you're taken by the music of the family. It's the same situation as with this band. I allow myself to be taken, because I have no prerequisites and arrangements."

We're sitting in the artist trailer next the Jazz Tent, immediately following this year's triumphant Astral Project Jazz Fest performance. These guys remember when playing the Fest meant looking out on a small crowd dancing in the mud. Today, an overflowing tent gave the band huge ovations for their set, which mostly featured new songs from VoodooBop, including a soft, fragile ballad, "Old Folks," sung with bitter-sweet charm by Vidacovich.

"You can just sit up there with that much energy from the audience, and the music plays itself, for me," he says.

I ask him about the moment during the tune "Sombras en la Noche (Shadows in the Night)," when he pulled out his key-ring and began shaking it into the mic, washing the symbols and toms with it for great effect.

"I forgot my percussion instruments, so that was the first thing I could think of that worked," he says.

"Good thing he didn't forget his keys," jokes Masakowski.

"What's really cool is that most of my percussion instruments are made out of old keys," Vidacovich says. The room erupts

in laughter, and Masakowski chimes in, "Yeah, from places you've been evicted from."

Kidding aside, it's this endless inventiveness and finesse that makes Vidacovich such an astonishing drummer. He coaxes new sounds from his kit with each roll and splash, incorporating New Orleans street beats and other dance rhythms to keep listeners on their toes. Time is kept with laid back swing, but he's also constantly in flux, responding fluidly to the music around him. You can see it in his posture and crazed facial expressions: total and immediate responsiveness to the moment at hand.

"One of the beauties of this band is that you can hit something you don't want to hear and one of the other guys will cover it up," says Singleton. "Johnny's an expert at that. He can erase clams like no one I've ever heard. That's what makes him one of the most brilliant accompanists that I've encountered in my entire life. I'm pretty much convinced it's almost a hundred percent unconscious. He's just being so subservient to the good of the music that if something comes by that needs to be erased, he will do it."

There is no complacency in Vidacovich' playing; he is perpetually seeking the next musical

peak. Asked whether he thinks this year's Jazz Fest performance was the band's best ever, Johnny replies, "I never really

call the best one the best one, because I'm always hoping for one to be better. I can only say that today's is the second best.

If you want to know when the best performance was, it's next year."

Just then David Torkanowsky struts into the room, causing a seismic shift in the mood. Everyone is suddenly alert, as though an invisible

grenade is being tossed around. Torkanowsky's aura of mischief and unpredictability creates a spontaneous atmosphere that is

a big part of his creative power within the band. He keeps people on their toes, forcing them to take chances. On piano, he can

range from edgy, abstract dissonance to romantic classicism to romping boogie-woogie (and often does within a single solo).

But no matter what he plays, it is always intense.

Scrambling through my notes to find a question, I ask him what he thinks has changed most with the band over the years, and what has remained the same. He replies, "What's changed the most? The depth and profundity of our communication has just changed so much for the better. And what has stayed the same? The money."

This causes a roar of laughter from the other guys, but also spawns an interesting discussion. After all, why hasn't this totally unique, immensely talented band received the recognition (and corresponding pay) that it deserves? The most obvious reason is that, until recently, they were so consumed with making the music that they mostly ignored the business end. They were also constantly distracted by all their jobs as sidemen, music professors (in Dagradi and Masakowski's case), film scorers and record producers (in the case of Torkanowsky, who produces records for Diane Reeves).

Only in the last several years has Astral Project taken such preliminary steps as hiring a manager and booking agent, and it has already paid off. They are finally receiving serious recognition in the national press, and they signed with independent label Compass Records, who last year released Elevado, the group's second album (the first, their self-produced, eponymous debut, came out in '94). This year, the band quickly followed up with VoodooBop, which was one of the top sellers at the Jazz Fest. In June, they'll benefit from primo exposure when they go out on a mid-western festival tour with their old friend, internationally acclaimed jazz/pop vocalist and classical conductor Bobby McFerrin. (McFerrin used to sit in regularly with Astral Project, back when he lived in New Orleans in 1979.)

Does this mean the band is working towards a point where Astral Project is the "main gig" and everything else is secondary?

"That would certainly be the Mount Olympus of our efforts," says Torkanowsky. Vidacovich agrees, "Yes, because of the amount of joy we get from the work, the actual musical work is a joy, it's not a labor at all. It's like a super sport, you know, like playing ball with guys who really know how to play ball. It's like the ball just stays in bounds. As long as we keep the ball in bounds, we're cool."

But despite these positive developments, the members of Astral Project know the odds are stacked against them. Their music doesn't fall into any easily marketed category, even within jazz, which, for the last twenty years, has increasingly focused on young, emerging artists and stressed a conservative, historically self-conscious approach.

"When I came up it was ultra-taboo to align yourself with any tradition, and now its the opposite," says Singleton. "Now it's become popular, but in some ways I think it's coming back around. You see a lot of these jam bands and it seems like people are eager to hear unique and original statements, and that's why I think our popularity is growing. The whole doctrinaire approach to improvising has pretty much played itself out."

During Jazz Fest, Singleton participated in a late night "Superjam" concert at the Howlin' Wolf, which brought him together with John Medeski, Michael Ray, Marc Ribot, Stanton Moore and others, and which drew a large, young crowd. "There were a thousand people there, you couldn't get in, and hundreds of people in the street. It was totally improvised and the audience was with us. It reminded me of an Astral Project concert, where we go completely out, yet the audience is still with you because you set them up for that, you set them up for the unexpected, and when you come back with the groove, they're ready for that, too. But those weren't twenty year old kids on the bandstand. They were just as gray as this band, more so. It's not about age. People are hungry for something that has the energy that comes with a unique statement, a statement that is not some slavish tribute to iconoclasts of the past."

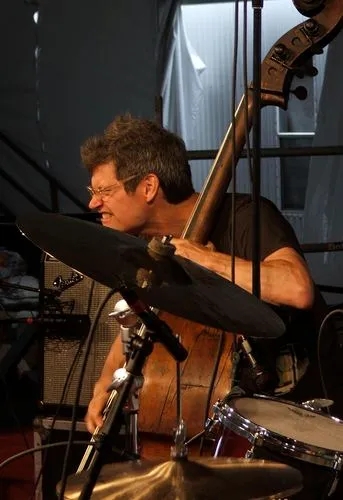

Singleton does far more than just talk about breaking new ground. Not only is he one of the few bassists who can play convincing funk on the upright, his solos and compositions consistently push the envelop. The last cut on the new record, his "The Queen Is Slave To No Man," for example, has no preconceived form except for the intro and ending, forcing the musicians to instantly compose new material every time it's played. His side project, Three Now Four, is geared even more towards jettisoning the established forms.

"I think there is a growing public that loves to see musicians on the high wire act and see us going for something," says Singleton. "I mean, you can prop up some museum piece for only so many years before people start to smell the dead fish. It's like, 'Come on, where's the new stuff? What are you really bringing to the party?'"

On the final Sunday night of Jazz Fest at Snug Harbor, Astral Project brings everything to the party. Tired of playing songs from the new VoodooBop record all Jazz Fest, they decide to shake things up a little by dipping into the well, dusting off a few tunes like "Bongo Joe" and "Hector's Lecture" that they haven't played in five years, and reinvigorating them. The five members dive in with an almost reckless abandon and the music gets white-hot very quickly. Soon, the audience is afraid to clap after each solo for fear of missing the next equally intense moment. At one point, Torkanowsky is making all sorts of percussion sounds on the piano, muting strings, beating on the wood, slamming the keyboard lid, anything to create fresh syncopation. Singleton is hunched over his bass, eyes closed, face contorted into painful ecstasy.

"It's very pleasurable, it's sometimes painful and it's everything in between," says Singleton later, attempting to describe how it feels to be up there. "It can be funny, also. Musical humor is kind of a funny idea, but it happens. You end up hitting a cliche that everybody knows and everybody laughs because that came out. There are many exquisite moments and there are bad times, too, when you hear yourself play something that is distasteful and you have to deal with it. The jazz masters say you can hit any note as long as you justify it with the next note. Just don't stop."

| Word of mouth about Astral Project | TOP |

By Chet Williamson

What's in a name? Not enough to hide the talents of Astral Project. Last year, when my local jazz organization booked Astral Project

as part of their concert series, I was hesitant. I wasn't familiar with the group, and the name made me think of some third stream,

smooth jazz aggregation, maybe with some wimpy electronic keyboard, a drummer who used brushes exclusively, an electric bassist, and,

if we were lucky, a front man, probably using a muted trumpet or a soprano sax. The music would probably be weavy, indistinct

melodies, and riffs that repeated over and over again and droned away into silence.

Boy, was I ever wrong.

Astral Project proved to be one of the most kickass bands I had ever heard. From out of New Orleans, these five guys played with

all the passion and fire associated with that city's wide range of music, and proved themselves instant contenders. I quickly

snapped up their CD, Elevado, played it until the aluminum melted, and I'm happy to announce their new CD, VooDooBop.

Down Beat

"One of the most distinctive and cohesive quintets in jazz of the '90s."

Offbeat

"The finest modern jazz ensemble in New Orleans, and undoubtedly one of themost unique jazz groups, period."

Chicago Tribune

"Like New Orleans itself, Astral Project blends a thousand influences into an alluring identity all its own."

By Kristin Ciccone

Being that after twenty some odd years of performing together Astral Project has cultivated their improvisational abilities to create tightly woven grooves, this is one show you definitely won't want to miss. To experience the otherworldliness of Astral Project for yourself, check out New Orleans' best kept secret in a venue near you.

By James Thompson

True to the original spirit of jazz, Astral Project creates real tunes -- memorable melodies -- while giving the musicians freedom to incorporate influences from all sources. Like a flock of birds in flight, the group shifts direction with an ease so uncanny it seems to verge on telepathy. It's an ease that can come only from special individuals who have spent 20 years improvising together. "If I close my eyes," says James Singleton, "I can learn more, get more. You find it's a transcendent experience. It's a s piritual experience in a way. Because you find you become part of a larger thing. It reinforces your faith - in God and existence, human existence. It heals you."

By Kevin Forest Moreau

Together, however, they make up one of the most adventurous and enduring modern jazz groups currently in circulation. Throughout more than 20 years and with a mere handful of albums, the quintet has expanded the boundaries of the form, able to improvise in beautiful and mesmerizing directions instantaneously. That edge-of-the-pants instinct will no doubt help the quartet weather the loss of keyboardist David Torkanowsky, who has left to pursue other projects.

By Ed Keane

These five veteran musicians -- known as tops on their instruments in jazz-rich New Orleans -- bring a wealth of diverse experience to the bandstand which has helped gained them features with NPR's Jazz Set with Branford Marsalis and profiles in Down Beat and Jazz Times. A story in The Chicago Tribune said, "Like New Orleans itself, Astral Project blends a thousand influences into an alluring identity all its own." They also bring strong ideas about the music they make together. For them, music is a group search for a higher plane of understanding. It is not about formality or classicism, musical boundaries or some misguided dogma on what constitutes "real" jazz.

By Howard Reich

To many listeners, New Orleans jazz invariably means Preservation Hall and marching brass bands but a more cutting edge school of jazz is also flourishing in the Crescent City and at its roots is Astral Project. This band brings certain elements of the city's distingushed musical tradition into everything played, and it may help explain its appeal. Certainly the New Orleans backbeats and parade rhythms make much of the band's pungent dissonances and unorthodox improvisations easier to embrace. Whether the band is playing angular lines in "Sidewalk strut" or complex chords in "Bongo Joe," two popular tunes from its large repertoire of original music, New Orleans' rich vocabulary of swing rhythms keeps the music breezily coursing forward.

As Scott Aiges of the Times Picayune wrote , "Astral Project squeezes so many styles ao efficently into improvisations that there is only one lable for the band's sound (other than heavenly): modern New Orleans music." Also according to Aiges, "Astral Project is the best group in the city." Which is why the ensemble has won just about every award the city of New Orleans has to offer, including Best CD in the 1995 Big Easy Awards for its self-titled debut album: Best Modern Jazz Group in the 1994 New Orleans People's Choice Awards and first place in the 1992 Cognac Hennessy Best of New Orleans Jazz Competition. Astral Project's line-up includes Steve Masakowski, one of the most accomplished jazz guitarist and the versatile keyboardist, David Torkanowsky.

| Awards for Astral Project | TOP |

2000 Big Easy Awards

Album of the Year: "Voodoo Bop"

1999 Down Beat Critics Poll

Acoustic Group Deserving Wider Recognition (third place)

1999 OffBeat Magazine Best of the Beat Readers Poll

Best Modern Jazz Group

1998 OffBeat Magazine Best of the Beat Readers Poll

Best Overall Group, Best Modern Jazz Group,

Best Modern Jazz Album : "Elevado"

1998 Big Easy Awards

Best Modern Jazz Group

1997 OffBeat Magazine Best of the Beat Readers Poll

Best Modern Jazz Group

1996 OffBeat Magazine Best of the Beat Readers Poll

Best Modern Jazz Group

Best Saxophonist: Tony Dagradi

Best Guitarist: Steve Masakowski

Best Bassist: James Singleton

Best Drummer: John Vidcovich

1995 Big Easy Awards

Album of the Year: "Astral Project: New Orleans, LA"

1994 New Orleans Peoples' Choice Awards

Best Modern Jazz Group

1993 Big Easy Awards

Best Modern Jazz Group

1992 Cognac Hennessey Best of New Orleans

First Place| Higher Fusion - The New Orleans Modern-Jazz Group Astral Project | TOP |

By David Lasocki

In September 2002, my wife Lilin and I went to a concert simply because it was sponsored by

our local jazz association, Jazz From Bloomington. I’d never heard of the group or its members

before. The name Astral Project made it sound like some New Age outfit writing a Weather

Report on the stratosphere. The concert poster, in sharp contrast, promised a mixture of jazz

with R&B and “a thousand influences.” I feared the worst: Medeski Martin & Wood performing

“Fire on the Bayou” for Music from the Hearts of Space.

In September 2002, my wife Lilin and I went to a concert simply because it was sponsored by

our local jazz association, Jazz From Bloomington. I’d never heard of the group or its members

before. The name Astral Project made it sound like some New Age outfit writing a Weather

Report on the stratosphere. The concert poster, in sharp contrast, promised a mixture of jazz

with R&B and “a thousand influences.” I feared the worst: Medeski Martin & Wood performing

“Fire on the Bayou” for Music from the Hearts of Space.

The concert confounded all my expectations. My visual impressions, especially, of

that momentous evening remain with me almost ten years later. John Vidacovich “on the drums

and the cymbals,” long and lean in a T-shirt and jeans, loose-limbed and loose-necked, ultra-

relaxed, dancing with his entire being, switching the beat in a trice from bop to Second Line to

funk to rock. James Singleton, John’s “main man” on the bass, in an oversize red-and-

orange check jacket, grimacing with fervor, shaking his mop of hair, pounding demonically,

slapping the strings, twisting from side to side, soaking up the groove. Steve Masakowski

“on the guitar,” a tall Mr. Cool, shifting lightly from foot to foot, mouthing his lines, moving

smoothly from rapid straight electric runs to silver sustained synthesized sounds. Tony

Dagradi, “our fearless leader,” upfront with his weather-beaten tenor sax, concentration

personified, eyes closed, rocking forward and back, mouth muscles bulging, reaching for the

stars. At first, the music’s energy—its chi—felt thick, like making love with the room, then it

Poster for the concert that drew the author in: John Waldron Arts Center, Bloomington, Indiana, 18

September 2002; from left to right, John Vidacovich, Tony Dagradi, Steve Masakowski, James Singleton

spread out high and wide, pushing up the roof and stretching out the walls. The interplay

among the four musicians was instant, yet flexible, like a web responding to the slightest touch.

Lilin, a grin now permanently planted on her lips, leaned to me and whispered, “This is real

chamber music.”

At intermission, Tony stayed behind and chatted with the audience. He accepted my

compliments with a nod and a smile. I asked him how long the group had been together

to achieve such rapport. “This is our 25th year.” I figured that might be unprecedented in

jazz.

At intermission, Tony stayed behind and chatted with the audience. He accepted my

compliments with a nod and a smile. I asked him how long the group had been together

to achieve such rapport. “This is our 25th year.” I figured that might be unprecedented in

jazz.

I bought the spiral-bound sheet music for the group’s latest CD, Big Shot, and got it autographed by all four members. Tony signed “Love, Light + Music.” John wrote “Peace + Love” with a Ban-the-Bomb sign after his name. The second half of the concert was even more intense than the first, taking me someplace I’d never been before in any kind of music, only in healing sessions, beyond even the astral plane, into the subtle realms of consciousness.

That concert made me an instant Astral Project fan, in both senses of the term—fanatic as well as enthusiast. I began to buy all the members’ CDs, collective and individual. Wolfgang Kurth, who hosts a website celebrating the group, sent me some recordings of live concerts. I quickly learned that until recently the group had been a quintet: the pianist David Torkanowsky (“Tork”) left in May 2001. I wrote to Tony by e-mail. He received my lavish praise soberly and, in response to a query, listed some CDs by other leaders on which he had taken significant solos. Generously, he sent me his last copy of Astral Project’s New Orleans LA CD, “the black-and- white one,” now out of print.

In October 2003, Astral Project came to Bloomington again. One year on, the group had become even more accustomed to playing without Tork. The sense of being a quartet was stronger, the interplay more elastic, the solos more inspired, the higher realms more present. I have never been to a finer concert. Lilin and I made breakfast for Tony that day, then dinner for the whole group after the concert, ending after midnight. My consciousness soared into the causal plane as I washed and chopped the vegetables. The four men were friendly, appreciative of our efforts, pleased to have a home to go to on the road. Before dinner, John played cars with our 2-year-old son Lucien; after dinner he was kind to Lilin’s 13-year-old son Garrett— gave him an Astral Project T-shirt and a copy of Big Shot. I have spent my adult life, forty-five years, writing about woodwind instruments in classical music.

At the same time, I have had a parallel life as a jazz fan. A sabbatical from my job as music reference librarian at Indiana University in spring 2004 gave me a chance to sit back from my usual research and consider putting my love of jazz into print. I wrote a short article—a poem with commentary—about the pianist and composer Uri Caine.

Then, going for broke, I approached Tony about writing a book on Astral Project. He and the other three members readily agreed to participate. I was both touched and amused when James said to me, during a performance at the Green Mill, Chicago, in March 2004: “We’re so glad you’re writing this book now. Most jazz musicians get written about when they’re old or dead. We’re in our prime....” I couldn’t have anticipated that my research period would coincide with Hurricane Katrina in August 2005, a catastrophe that scattered the four to the winds and brought the futures of both the group and New Orleans itself into question.

After I had written 800 single-spaced pages of material about Astral Project and its members, I had to spend some time contemplating what to do with it all. The result is: Five books on Astral Project and its members. The present book is a general history of the group, with a chapter containing brief bios of the members. The other four books are detailed biographies of Tony, Steve, James, and John.

David Lasocki Homepage